[ad_1]

As a train slowed

to take a hill outside a riverside city in communist Romania, about 20 young

men leapt off and ran into the cornfields.

The fleeing men had planned to remove their clothes and tie them to their backs before going into the Danube River, but the dreadful sound of guards and dogs in hot pursuit changed their minds.

Plunging into the

frigid water, George Tanase swam like mad, periodically checking for bullet

wounds—in case adrenaline prevented him from feeling them—and trying,

unsuccessfully, to kick off his waterlogged shoes.

Carried swiftly downstream by the current, George, exhausted, climbed onto what he hoped was the opposite bank of the Danube.

He found himself

face to face with the barrel end of a soldier’s rifle. He took hold of it and

was pulled up onto the bank. Out of the soldier’s mouth came the familiar sound

of Romanian.

It was Sept. 11,

1951.

***

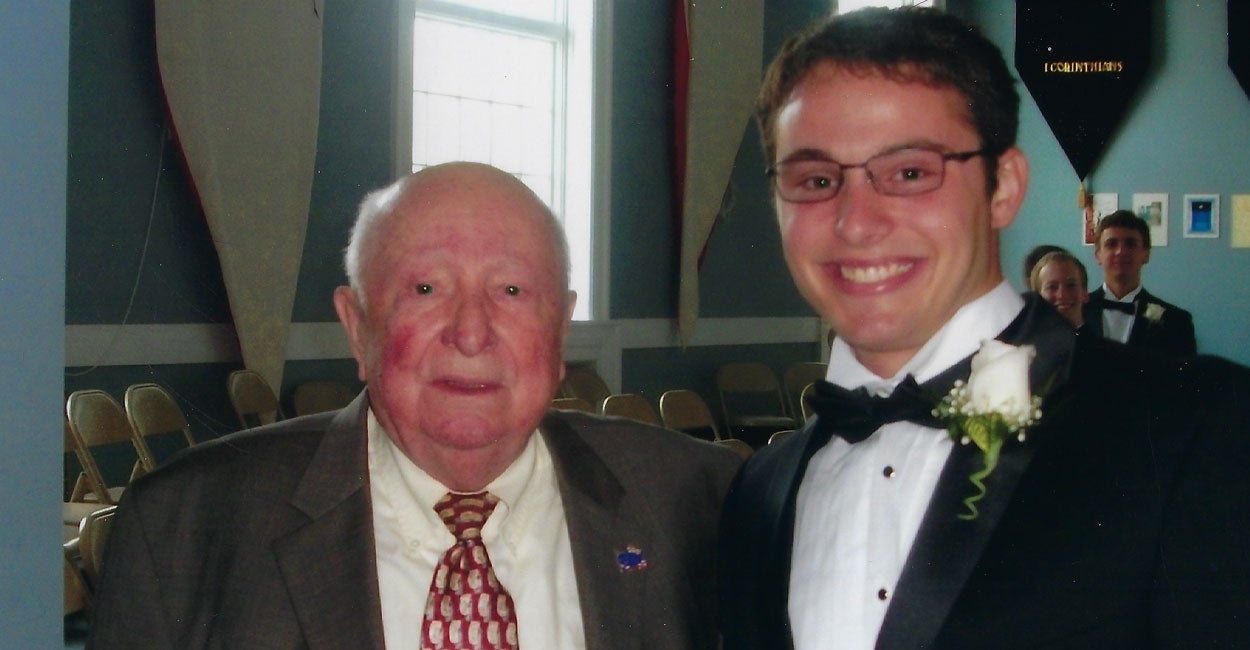

As I sipped slivovitz with my grandfather last Thanksgiving, more than 68 years later, I reflected on all that George Tanase had done in his 90 years.

“Poppy,” my mother’s father, retired only in 2019. His work as a sought-after electrical engineer played an outsize role in his life, and in my memories of him.

But there were

also stories such as this one from Poppy’s past that, to a boy, had seemed as

fanciful as Captain Nemo’s Nautilus.

My mother and a cousin had made attempts to record some of these stories for

posterity, but no one had gotten beyond rough sketches.

Feeling the

urgency of Poppy’s advanced age, I pulled the seemingly ancient briefcase off

the shelf in my office, where it had rested since being shuffled from some

other out-of-the-way cubbyhole. I extracted loose papers, a notepad, cassette

tapes, and a tape recorder.

I dusted off my

research chops and began sifting through the 40-odd pages of heavily

hand-edited narrative my mother had written and the almost four hours of interviews

with Poppy that my cousin had recorded on five sides of cassette tape.

Knowing that

context is king, I made quick work of Keith Hitchens’ excellent “A Concise History of Romania,”

from which I gleaned crucial perspective and a framework upon which to

construct an accurate account of a man whose life belongs to the history of

that people caught between the Scylla and Charybdis of East and West.

And so this is my telling, based on Poppy’s accounts, of his escape from the conquered homeland of his youth to the fabled land of unbridled opportunity.

Born

Into the Bourgeosie

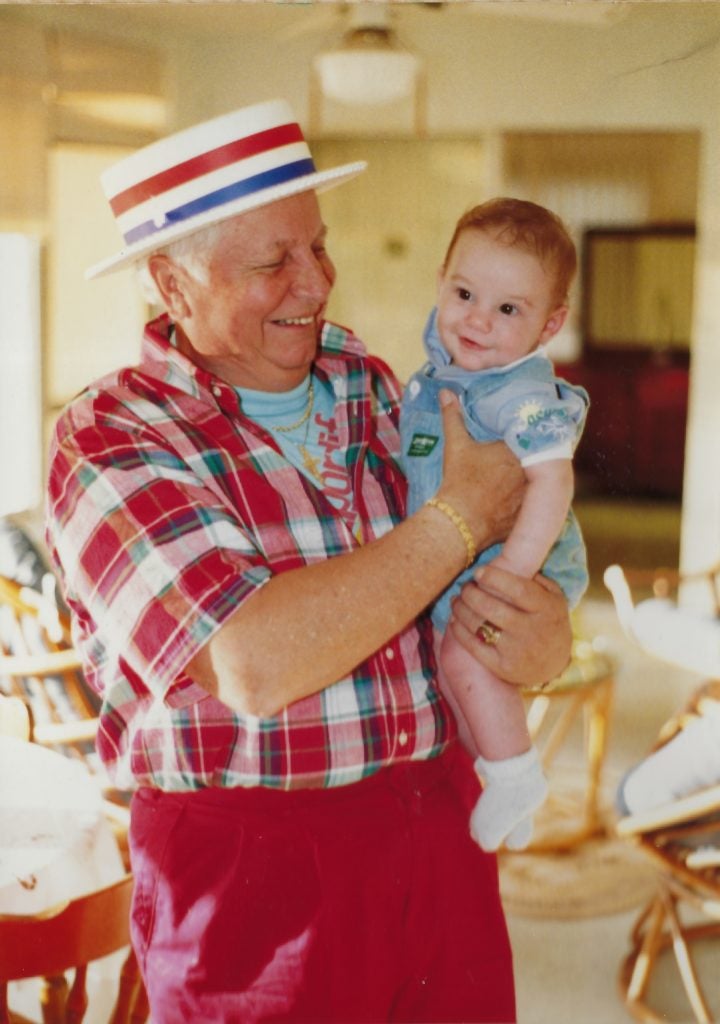

George Peter Tanase was born the third of four children of a provincial tax collector and a part-time math teacher, on April 14, 1929, in the northeast Romanian city of Mileanca.

George’s parents

were fairly typical members of the burgeoning bourgeoisie in Romania, splitting

their time between a house in the city and a farm and vineyard in the

surrounding countryside.

Showing promise in mathematics, in 1947, George began studying architecture at the Institute Polytechnic in Bucharest, where he would graduate in 1951.

In 1941, watching from the window of his seminary boarding school in Iasi, Romania’s second-largest city, George had observed the German and Romanian armies march east on their way to free the region of Bessarabia from Russia.

Three years later, he left for home when the Romanian government, heavily influenced by Russian occupiers, shut down all private schools.

When George returned to complete his studies in Iasi, it was at a military academy run by the state.

The Soviet

Union’s Red Army, now as an “ally,” entered Romania on Aug. 31, 1944. A little

over three years later, on Dec. 30, 1947, the communists declared the creation

of the People’s Republic of Romania. It was less than a half a year after my

grandfather’s arrival at Institute Polytechnic.

The

Grip of Communism

Communism was

unpopular in Romania, a mostly democratic and parliamentarian nation.

But although

Paris had been the spiritual home of the country’s liberal political

architects, those whose affinity for Soviet dictator Josef Stalin had drawn

them to Moscow now returned to rebuild the state in its image.

Children were

easy targets because they could not remember an alternative. Opposition to the

communists from those who could remember was ubiquitous, but no match for the

iron-clad will of Stalin and his Romanian apostles.

Executions,

imprisonments, disappearances, and forced relocation slowly, but surely,

convinced many Romanians of the expedience of forgetfulness, at least in

public.

The communists dismantled religion, history, patriotism, music, and burgeoning aspiration to be a part of western European civilization that had characterized this relatively free people. They replaced these frameworks of identity with a contrived narrative fashioned by and for Russia.

Poppy recalled

hearing of children being told to pray to God and then to Stalin, with candy

brought to them only after they said the second prayer.

Worse, there was

no incentive for those in power to return to the old order, as they owed

everything to Stalin.

Before he was allowed to register for fall classes, George was required to do a month of “volunteer” work each summer.

The very people who previously worked for the Tanase family seized their possessions and occupied their land; George’s father was transferred to Iasi, where he served an increasingly centralized government bureaucracy.

Joining the Resistance

From the outset,

it was clear to George that the traitorous Romanians were not altruistic

ideologues, but covetous hypocrites for whom the dictate was “What’s yours is

mine and what’s mine is mine.”

George knew that Romania,

one of the world’s largest oil producers, should not struggle to keep its

people warm in the winter. In an overwhelmingly agrarian nation where most of

the arable land was devoted to grains, a lack of bread at the end of a half-day

long line was a sign of foul play: Drought or no, it should not have been

possible to starve in a bread basket.

George and many

university peers joined the “haiduchii,” or outlaws, who, with other relatively

small resistance groups, opposed communism. The students soberly considered

revolution, but they were playing a dangerous game and the party was not

passive in trying to infiltrate their ranks.

Those the

Romanian security forces could not silence or kill, they used as unwitting

honeypots.

As things got

worse, the students’ conversations shifted to the possibility of escape.

Informed that, upon graduation, they would be required to work on a project at

the Iron Gates of the Danube River, those familiar with the train route

recalled a hill where the train would slow, making it possible to jump off

safely.

The Yugoslavian

border was just across the Danube. The students had read into Yugoslavian

leader Josip Broz Tito’s split with Stalin a rapprochement with the Allied

powers and a possible American presence in Yugoslavia.

In fact, although Tito no longer was a puppet of the Cominform, or Communist Information Bureau, he remained a committed Marxist and relatively uncommitted to either power bloc.

Detained

in Communist Yugoslavia

Which takes us

back to that September day in 1951 when, confused, fatigued, and greeted with

the native tongue of the nation he had tried to escape, George passed out on

the far bank of the Danube.

Unbeknownst to

him, he was one of only five of the 20 or so men who jumped from the train that

day to make it to the Yugoslavian side of that famed river.

Security forces

took George to be interrogated in Kragujevac, a major city that had been

liberated from the Nazis in October 1944.

The Yugoslavian

communists were not above returning refugees to the Romanian communists in

exchange for Romanian salt. But George hoped that his contact with the

Yugoslavian ambassador to Romania at the embassy in Bucharest, Romania’s

capital, would verify his identity and ingratiate him with his captors.

For the time

being, the Yugoslavians detained him indefinitely alongside their native

dissidents in a makeshift cell in the basement of a bank in Vršac, near the

Romanian border. Here, George met Aural Vlaicu, a former pilot of King Michael

I, who, harboring similar misperceptions about Tito’s allegiances, had flown

the Romanian king’s plane to Yugoslavia’s capital, Belgrade.

Given so little

food that he longed to fall asleep, if only to dream of his mother’s cooking,

and deprived of a shower or bath for nearly two months, George fell ill.

Not long after, a surprise humanitarian inspection, spurred by an escaped prisoner’s complaint to the United Nations, discovered him in a pitiable state.

Escaping a

Refugee Camp

The inspectors took George to a hotel, where he was given food and allowed to bathe. They placed him in a refugee camp in Kruševac, where he was assigned a job as a draftsman at a nearby factory.

There, he and Aural forged transfer documents; they spent their

evenings casing the operations of a train that regularly left the city.

A guard always followed George and Aural, warning them that escape

was impossible. George, undaunted, told the guard that he would do just that.

Few Romanians willing to risk death to escape their own nation’s

first communist leader, Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej,

were content to remain in thrall to Yugoslavia’s Tito for very long. But the

road to freedom was treacherous, and many who made it on one train were caught

on the next, at a station, or at the border.

George and Aural

were careful students of their countrymen’s misfortunes and steeled themselves against

even the slightest negligence. One night, their guard was distracted and didn’t

bother to follow them, so George and Aural waited for the “all aboard” call and

climbed atop the train.

Once in Belgrade,

they spent the night in a park to avoid station guards. On the third attempt, they

convinced a passerby to purchase tickets for the night train to Zagreb,

Yugoslavia, today the capital of Croatia.

Even though the

two young men had papers authorizing their travel, they didn’t want to rely on

those. And so, once the conductor had checked their tickets, George and Aural

waited for those who checked papers to enter and then avoided them by slipping

out the back of the car.

They climbed up and across the roof, and entered the opposite end of the same car, where the presumption would be that someone had checked their papers. This was risky—Aural was almost caught when he waited too long to begin climbing—but it worked.

Encounter

With the CIA

Arriving in

Zagreb, the pair used their forged papers to purchase tickets to Yugoslavia’s

border with Trieste. Soon after their departure and two stations early, they

jumped and hid in some bushes until dark. Then they began to make careful

progress toward a sparsely guarded section.

Accidentally, but

quite fortuitously, George and Aural came upon a group that was sympathetic to

their cause. The encounter bought them a smoke and a friendly warning that

their intended route would ensure capture.

Following this advice, the two young men arrived safely at the crest of a hill, from where they could see Trieste. In a pleasant twist on their earlier arrival in Yugoslavia, the first thing George and Aural heard in this free land was the “Buna dimeneata” (or “Good morning”) of some Romanian refugees.

After they

reported to the police, as instructed, authorities took them to a camp where,

after clearance by intelligence representatives, they could apply to immigrate

to Canada, the United States, New Zealand, or Australia.

The CIA was

recruiting spies, but an American colonel of Romanian descent persuaded George

that Canada’s quota space and need for professionals made it the better initial

port of entry to the free world.

Poppy told me

that he never wavered in his desire to come to the States, and did so as soon

as he could, but that he took the colonel’s advice.

Those who applied, qualified, and were trained as spies by the CIA parachuted into the mountains outside Brasov, Romania, only to be captured, executed, and hung from the streetlamps as an example.

The

Fire of Freedom

About 140 miles away, hearing propaganda about the fate of some American-trained spies, George’s mother—my great-grandmother— disguised herself as a peasant and sneaked aboard a train from Iasi to see if her son was one of them.

George Tanase had avoided this one last snare, but it would be nine long years before his mother knew he was alive … and free.

I recently spoke to Poppy about my own

grand vision, a vision full of risk and danger and derided by many denizens of

middle-class suburbia. I saw in my grandfather’s eyes a fire undiminished by

age.

In that fiery gaze, I came to

understand what was truly great about these United States. What makes a man or

nation free is not the mere absence of tyranny, but the ability, unadulterated

by cowardice or complacency, to do what ought to be done.

No nation has remained merely free

that has failed to remain truly free.

If America is to remain merely free, she must be the homeland of those with the fire of true freedom in their eyes—whether born in Mileanca, Romania, or Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

[ad_2]

Read the Original Article Here